Alopecia, thinning hair, and hair loss are one of the common reasons why cats are brought to the veterinary clinic. First, it must be determined whether alopecia is indeed pathological hair loss. Owners are often worried about increased hair loss, but as long as the animal has no symptoms of hair loss/hypohairiness and no other clinical symptoms (such as itching), this hair loss is physiological. Persian cats may experience focal hair loss during moult. Some breeds or certain parts may have normal hair loss/oligotrichosis, such as ear hair loss in older Siamese cats, hairlessness or varying degrees of hair loss in Sphynx cats, and lack of hair in front of the ears in all breeds of cats. .

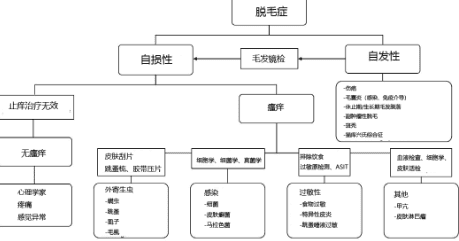

If pathological alopecia/oligotrichosis is indeed present, various differential diagnoses can be considered. Therefore, as with all animals affected by skin diseases, it is recommended that animals with alopecia are examined according to an established diagnostic protocol. The first step is always a detailed medical history discussion, preferably using a pre-printed medical history form that the owner can fill out in advance (waiting room). Based on this information, such as the age of the animal, what the initial symptoms of the skin problem were (which symptom came first: hair loss or itching?), skin lesions in other animals or humans it lives with, it can provide important information for building a differential diagnosis list. . After the clinical examination, an in-depth dermatological examination was performed to further examine the animal's skin from the nose to the tip of the tail for the presence of any lesions. For systemic diagnosis, it is helpful to classify possible causes of hair loss into "self-destructive" and "spontaneous" causes.

Some diseases may cause two forms of alopecia at the same time (such as dermatophytosis, cutaneous lymphoma). In some cases, on the one hand, the hair follicles are damaged, resulting in spontaneous hair loss, but at the same time there is pruritus (e.g., caused by secondary infection with dermatophytosis), resulting in self-destructive or secondary alopecia.

Autodestructive alopecia is easily diagnosed in animals that clearly exhibit an increased desire to groom. However, many cats tend to only engage in this frequent grooming when their owners are away. However, the presence of broken hairs on trichoscopy is suggestive of self-destructive alopecia due to licking.

Itching is the most common cause of self-destructive alopecia in cats. In adult animals, pruritus is most commonly caused by allergies; however, the presence of infection must be ruled out before initiating allergy evaluation. Therefore, the first step is to detect or rule out ectoparasites using a flea comb, superficial/deep skin scraping, and possibly tape wafers. In principle, fleas, lice, hairlice, chelicerae, ear mites (which can also leave the ear canal) and dorsal anal mites can cause itching. Additionally, Demodex Gotoyi does not live in hair follicles, but in the stratum corneum, and unlike other species of Demodex, it can cause intense itching in animals. Fleas can also cause hypersensitivity reactions. Even if parasitic infection is not confirmed, animals with itchy skin should receive ongoing ectoparasit prophylaxis effective against fleas and mites (e.g., isoxazolines). This way, flea allergy dermatitis can be diagnosed and treated at the same time. The next step is to evaluate bacterial and fungal infections through cytological, bacteriological, and mycological examinations. Dermatophytes may be the cause of pruritic and non-pruritic alopecia. Bacteria and Malassezia generally represent secondary infections. If normal skin flora or Malassezia are cultured, the number of microorganisms in the cytology can be used to determine whether it is just a problem of physiological colonization, or whether there is real excessive proliferation or Infect. Although Malassezia dermatitis is often found in dogs as a complication of allergies, in cats, Malassezia dermatitis usually indicates a more serious underlying disease, such as systemic infection or neoplasia. In addition to detecting infection, cytology can provide indications of non-infectious diseases, such as pemphigus foliaceus or cutaneous lymphoma.

If infection is not diagnosed, or if clinical symptoms do not improve with appropriate treatment, allergic disease should be strongly suspected. Since it is impossible to distinguish clinically which type of allergy it is, a food elimination provocation test is first used to check for food allergy. During an elimination diet for 8 to 12 weeks, only foods consisting of a single protein and carbohydrate source are fed. If judged, an elimination diet may select food ingredients that the animal has never eaten before. Since a "blindly" chosen diet may carry the risk of intolerance, food allergen testing is recommended when choosing protein and carbohydrate sources for an elimination diet. Based on the results, select proteins and carbohydrates that are negative for either IgE or IgG antibodies. Generally speaking, having written test results can also strengthen the owner's determination to stick to a strict diet. In addition, keeping a feeding diary can make the trial process more standardized. Since several studies have found undeclared protein content in commercial grains, the ideal elimination diet is one made from homemade grains. If this is not possible, a high quality hypoallergenic or hydrolyzed (peptide < 1 kDa) prescription diet should be used.

If a strict elimination diet for at least 8 weeks still cannot achieve satisfactory improvement in itching, focus on the differential diagnosis environment. Allergen sensitization (according to the new nomenclature FASS = Feline Atopic Skin Syndrome). The diagnosis of FASS is always clinical based on a detailed history, clinical findings, and exclusion of other pruritic conditions. Allergen testing (intradermal testing or serological IgE testing using the FcEpsilon Receptor Test®) is not a diagnostic test but is used to identify triggering allergens. The Itch Initial Screening Allergen Testing Package (test item number: #7105) can detect major categories of allergens such as dust mites, pollen and mold, and flea saliva. A flea saliva IgE test may also be used alone if there is strong clinical suspicion of flea saliva allergy. Allergen groups with positive test results can be further tested and identified (for further identification of pollen, select seasonal allergen inspection; for further identification of dust mites and mold, select year-round allergens). Allergen-specific antibodies (IgE) can also be tested for less common allergy triggers such as insects or the epithelium/feathers of various animals. For animals that live in the Mediterranean area or frequently travel there, there is also a specially developed package that takes into account the special flora of the Mediterranean. Malassezia IgE can also be tested if allergy to Malassezia is suspected. Finally, based on the research results, allergen-specific immunotherapy solutions can be customized.

Rare causes of pruritic autodestructive alopecia are hyperthyroidism and cutaneous lymphoma. For this reason, total serum thyroxine levels should be determined in older cats showing other clinical signs of hyperthyroxine before allergy testing is performed. In cases of suspected cutaneous lymphoma, cytology provides clues to cutaneous lymphoma, which requires biopsy to confirm the diagnosis.

Non-pruritic self-destructive alopecia occurs much less frequently than pruritic self-destructive alopecia. It may be caused by "psychiatric illness," pain, or neurological disease/paresthesia. Psychogenic alopecia is caused by stressors such as relocation, loss of a companion animal or caregiver, or a new family member, while pain and paresthesia are the result of trauma, musculoskeletal system disease, or neuropathy. A suspected diagnosis is made when the animal's intense desire to groom does not respond to anti-itching treatment. However, all causes of pruritic hair loss must be ruled out beforehand. In a study of 21 cats diagnosed with psychogenic alopecia, it was found that in only 2 of the animals, the hair loss was due to purely behavioral problems. Other animals have at least one other disease, such as food allergies and atopic dermatitis, which explains the frequent grooming behavior (Waisglass et al., 2006).

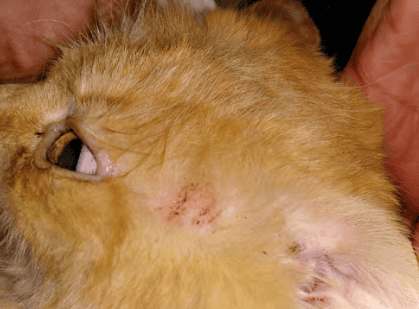

Spontaneous alopecia is rare compared to self-destructive alopecia. A diagnostic clue to spontaneous hair loss is the tendency of hairs at the edges of the lesion to be pulled out. First, it is necessary to determine whether the hair removal area may be a scar (such as trauma, repeated injection of glucocorticoids). A relatively common cause is folliculitis, which may be the result of an infection (eg, Demodex, dermatophytes, staphylococci) or an immune-mediated disease (eg, pemphigus, Figure 5). Hair follicles are damaged due to inflammation and hair falls out. Diffuse, non-inflammatory shedding can be triggered by extensive hair loss during the anagen (after a few days) or telogen (after one to three months) periods following severe mental or physical stress. Particularly in older animals, hair loss may occur in the course of neoplastic diseases (hepatobiliary cancer, pancreatic cancer), the main manifestations of which are complete hairlessness on the abdomen and waxy, shiny skin. Often, these animals also display systemic clinical signs. Diagnosis was confirmed using imaging techniques and histopathological examination of the tumor. Alopecia areata is a very rare form of hair loss in cats due to autoimmune destruction of hair follicles and is diagnosed by histopathological examination. Feline Cushing's syndrome is also a very rare disease. In addition to hair loss and thin, fragile skin, affected animals typically exhibit polydipsia/polyuria, polyphagia, pear-shaped abdomens, and, in about 80% of cases, uncontrolled diabetes. Diagnosis is made by a corresponding functional test of the serum (dexamethasone suppression test).

扫一扫微信交流

扫一扫微信交流

发布评论